Jump to a key chapter

The word 'epistolary' comes from the word 'epistle' (from Old French: epistle, Latin: epistola), meaning a letter.

Epistolary novel Definition

An epistolary novel can be told through letters, documents, journals, memoirs, diary entries, newspaper articles, notes, transcripts – in other words, it is told via any written form of communication. There may be dialogue and action in these communications, but these will tend to be described from the first person only. The reader is included in an intimate discourse that can allow them to see into the character's innermost thoughts or perspectives.

The epistolary novel can be traced back to ancient times; for example, The Works of Ovid contains embedded letters or journals.

An early example in English Literature is A Post with a Packet of Mad Letters by Nicholas Breton (1602), a collection of fictional letters between fathers and sons, sisters, friends, merchants and courtiers, which mostly offer advice or comfort. The only connection between the correspondents is that they have been found together in a lost mailbag.

James Howell, a poet and historian during the Restoration period, wrote Familiar Letters Domestic and Forren (1645-55), a collection of letters to (mostly) imaginary correspondents, describing historical events, court gossip, and legends (for instance, the Pied Piper of Hamelin).

Aphra Behn plays with the epistolary form in her Love Letters Between a Nobleman and his Sister (1684-1687). Set during the Monmouth Rebellion, the novel is part correspondence, part narrative, with letters mislaid, forged, or withheld.

The age of the Epistolary Novel

It was not until the 18th century that the epistolary novel evolved into a popular genre in Europe, with novelists like Johann von Goethe, Madame de Stael, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Samuel Richardson using the technique.

Samuel Richardson's three novels, all of which are epistolary, helped establish the epistolary novel in England:

Pamela (1740)

Clarissa (1748)

Sir Charles Grandison (1754)

Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded, follows Pamela, a maidservant, in her prudent navigation of a relationship with her late mistress's son, until ultimately she marries him. The story is narrated mostly through Pamela's letters and journal entries to her parents.

An immediate bestseller, Pamela was widely imitated - although not always admiringly: Henry Fielding published his satirical parody Shamela only five months after Pamela came out. In Shamela, also an epistolary novel, the virtuous Pamela is revealed to be in fact a very naughty woman who deliberately manipulates her wealthy master into marrying her. Fielding wrote his parody in protest at what he considered the moral hypocrisy of Pamela. We as readers discover the scheming character of Shamela/Pamela due to the epistolary form of the novel. Shamela's letters reveal her innermost thoughts and actions (which are concealed from the rest of the characters).

Note: Fielding wrote Shamela under the pseudonym of Conny Keyber.

Clarissa and Sir Charles Grandison both contain similar storylines, with kidnappings and attempted seductions as recurring elements.

In Clarissa, parental control is added to the mix, which contributes to the fatal climax - Clarissa, a young woman of virtue, resists the libertine Lovelace despite threats, kidnapping and violence. Ultimately, her health destroyed, she makes her will and dies in hiding. Lovelace is challenged to a duel and is fatally wounded, saying with his last breath "Let this expiate!”

Sir Charles Grandison, written in response to Henry Fielding's Tom Jones, shifts the focus to a positive male hero: Sir Charles rescues Harriet from abduction at a masked ball and leaves her in the care of his married sister. Although Charles and Harriet form an attachment, Charles has a previous understanding with Clementina, an Italian aristocrat. This is ultimately resolved when Clementina declares she cannot marry a non-Catholic. The novel ends with Charles marrying Harriet and their friendship with Clementina, who chooses to become a nun.

Note: Richardson was persuaded by many female friends to write a novel with a positive male lead.

Fanny Burney's Evelina (1778) is another example of the epistolary novel; combining social commentary with satire, it is a comedy of manners involving children switched at birth and high society, largely narrated through the eyes of a 17-year-old. It was very popular and admired by many members of the literary and fashionable world including Dr Johnson and Sheridan.

Leonora (1806) by Maria Edgeworth, explores the meaning of sensibility in two different female characters through their correspondence: the 'theatrical' Olivia from France and her more reserved English counterpart, Leonora.

Jane Austen also used the epistolary technique, especially in her early works, including Lady Susan and Mansfield Park.

19th-century Epistolary Fiction

As the novel grew in popularity, narrative techniques expanded. The omniscient narrator and the first- and third-person narrative style took over and the epistolary style was somewhat sidelined, with some notable exceptions, including:

- Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus

- The Moonstone

- Dracula

The whole of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein is narrated in letters from a sea voyager to his sister, where he transcribes Frankenstein's first-hand accounts.

Frankenstein

A sea voyager, Walton, writes home about how he has rescued a dying scientist called Frankenstein, who then tells his story of how he created a monstrous being 'The Creature' - the story flashes back to Frankenstein's student days, which are spent hunting the secret of life. Frankenstein builds a Creature from the bodies he obtains from dissection rooms and brings it to life. Horrified by what he has created, Frankenstein rejects the Creature, who disappears into the outside world. The story, after several murders and much travelling, ends with Frankenstein dying.

Walton closes the narrative with a description of a meeting with the 'Creature' who, informed of Frankenstein's demise, disappears on a raft across the waves until he is 'lost in darkness and distance'. (M. Shelley, Frankenstein, 1818)

Wilkie Collins developed a broader technique with his detective novel The Moonstone, one of the early major detective novels in English literature.

The Moonstone concerns the theft of an invaluable jewel at a family house in the countryside.

Most of the characters give first-hand witness accounts or statements, with the exception of Ezra Jennings, who uses a journal. Letters only crop up a couple of times.

The technique is explained by Franklin Blake, one of the main characters:

Starting from these plain facts, the idea is that we should all write the story of the Moonstone in turn—as far as our own personal experience extends, and no farther.

(Wilkie Collins, The Moonstone,1868)

This allows the reader to experience the action of the novel at first hand, through the eyes of each character as they take up the story.

Bram Stoker, in his vampire novel Dracula, follows a similar structure to Wilkie Collins in using different accounts from various character viewpoints through journals, diaries and letters. He also includes the latest in communication technology: telegrams and a phonograph diary, containing a recorded message from Dr van Helsing (a pre-cursor to current-day voicemail)

The novel opens with the journal of Jonathan Harker, a young solicitor travelling to Transylvania to settle a sale of land with a client called Count Dracula, who turns out to be a vampire. Harker narrowly escapes the Count's clutches and falls into a fever at a convent, where his fiancee Mina joins him and continues the story in her journal. Mina's journal also includes a news cutting that announces the appearance of the Demeter which counted the Count among its passengers.

The narrative is shared by five of the main characters and is concluded by Mina when all five characters unite with Dr Helsing in bringing down the Count.

The epistolary technique has risen in popularity with the arrival of the internet, and epistolary fiction can include text messages, emails, blog excerpts, voicemail transcripts.

Ladies of Letters.com (2201)

Ladies of Letters Log On (2002)

by Carole Hayman & Lou Wakefield

Part of a series of books (Ladies of Letters), these novels follow the witty, at times vitriolic, exchange of emails between two suburban widows who describe their escapades in amateur dramatics, family crises, and travels abroad.

House of Leaves (2000) by Mark Z. Danielewski, is also an epistolary novel that draws on media technology.

The first narrator (Johnny Truant) discovers a manuscript in a vacant apartment. The manuscript is by previous inhabitant Zampano and describes a documentary about a house that is bigger on the inside than on the outside. There are several different narrators including Johnny, Zampano, and members of the Navidson family who have lived in the house; the narratives take the form of a report, transcripts, records and notes.

The epistolary novel has also appeared in science-fiction:

The Martian (2011)

Sleeping Giants (2016)

Andy Weir's The Martian is narrated by means of a logbook, kept by botanist Mark Whatney after he is marooned on Mars.

A film version of The Martian came out in 2015.

Sleeping Giants by Sylvain Neuvel describes a physicist's search for the various parts of an ancient giant robot hidden across the Earth's surface. The narrative is a series of interviews and journals.

The epistolary novel offers the reader the opportunity to experience the story up close, to see through the character's eyes and experience their world intimately. Despite a lull in the 19th-20th century, the millennium and its technology have contributed to the genre's rebirth, opening up new avenues for storytellers to explore.

Epistolary fiction - Key takeaways

An epistolary novel is essentially a story told through letters

The epistolary novel developed during the 18th century and remained popular for much of the 19th century

The epistolary novel has regained popularity in the 21st century

Epistolary comes from the word 'epistle', meaning a letter

An epistolary novel can be told through letters, documents, journals, newspaper articles, transcripts etc

Samuel Richardson’s three novels, all of which are epistolary, helped establish the epistolary novel in England

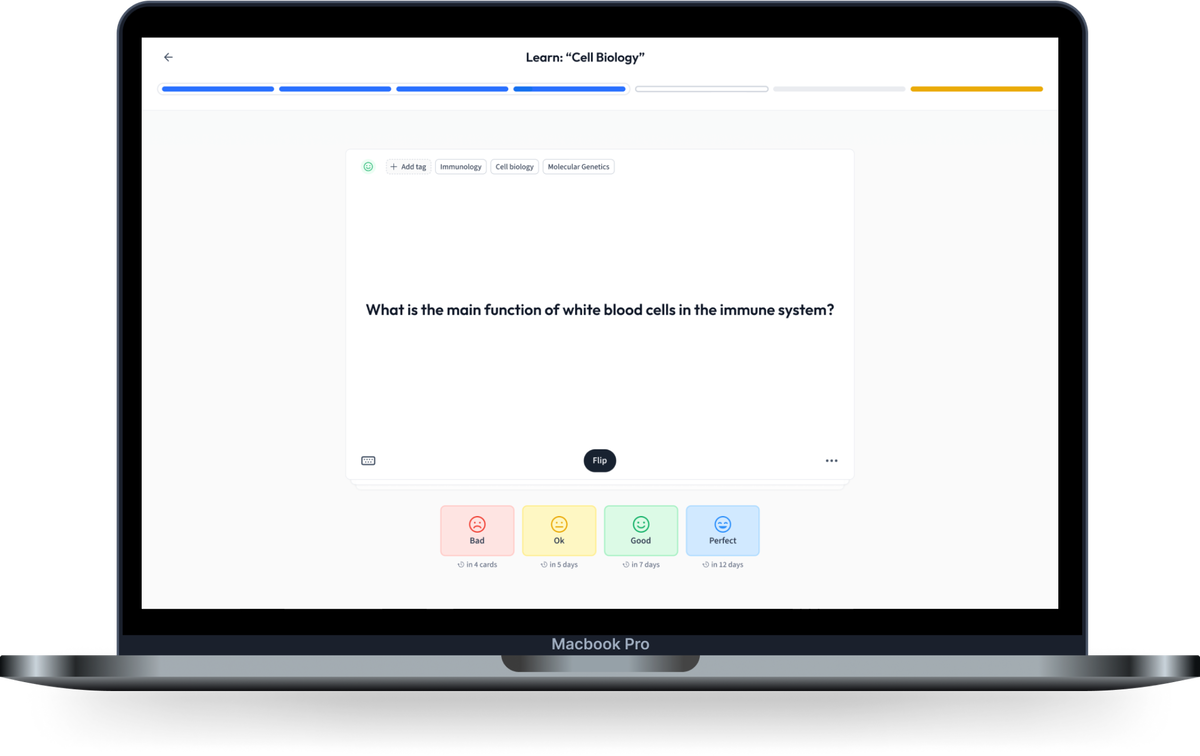

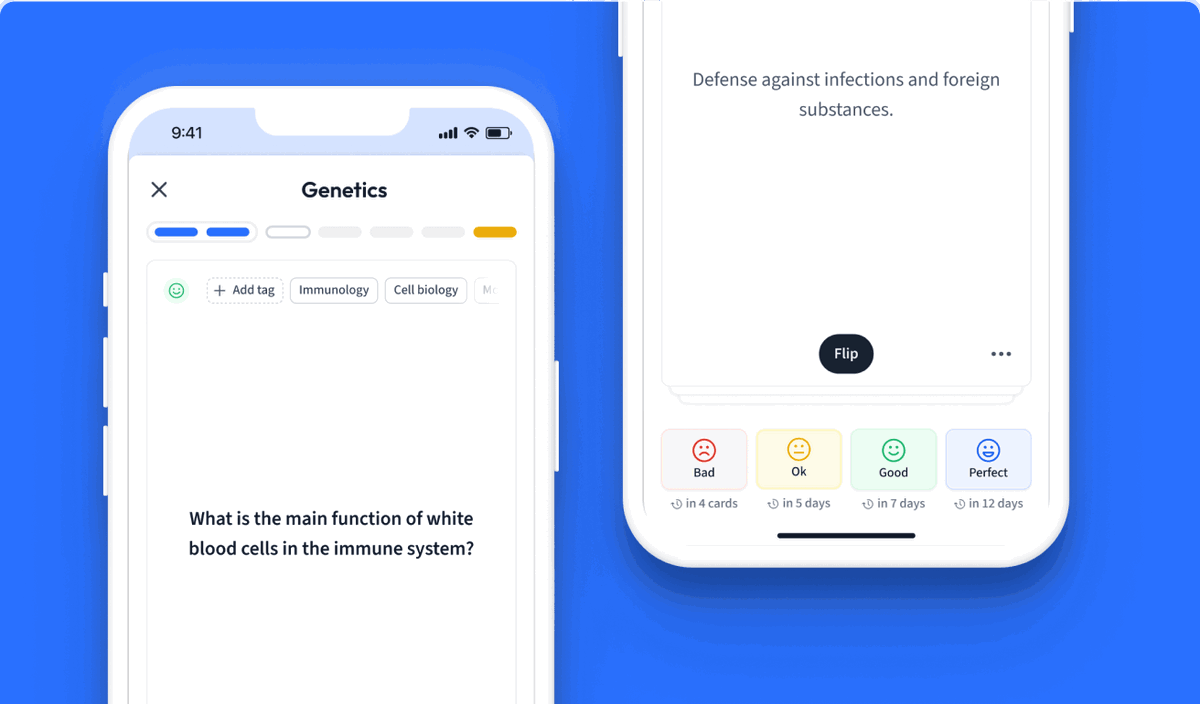

Learn with 2 Epistolary Fiction flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Epistolary Fiction

What is an epistolary novel?

An epistolary novel is a story told through letters, documents, journals, newspaper articles etc.

What does epistolary mean?

Epistolary comes from the word ‘epistle’, (from Old French: epistle, Latin: epistola) meaning a letter.

What is an example of an Epistolary Novel?

Richardson’s Clarissa, Shelley’s Frankenstein, Stoker’s Dracula.

What is Epistolary Fiction?

Epistolary fiction is any piece of literature that is narrated exclusively by means of letters, journals, diaries, documents etc.

How do you write Epistolary Fiction?

Explore different formats, like email, texting, as well as letters, journals; make sure every character has their own voice.

About StudySmarter

StudySmarter is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

Learn more